From Smoot to Trump: A Tariff Tale

Recent US action on tariffs has been meme-worthy, but history and economics suggest the concept of tariffs deserves a second look. Maybe even a serious one.

The “Liberation Day” tariff rollout is at best a comedy of errors — funny only if you ignore your declining retirement fund and the abrupt and global loss of confidence in American foreign policy.

But what if... the idea of strategic tariffs isn’t crazy?

Tariffs vs. Free Trade

A tariff is a tax on imports. Usually paid by the importing business (not the foreign country, despite what some are led to believe), it makes imported goods more expensive — and, ideally, gives domestic industries a leg up.

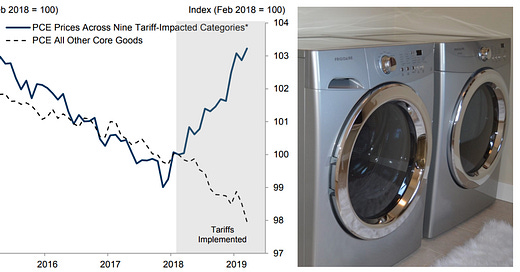

Tariffs definitely penalize domestic consumers. Remember what happened to washing machines, consumers, and the US economy when Trump tariffed 12.7% of imports in 2018:

The big question: Do tariffs work if the goal is to foster U.S. industry?

Since the 18th century, mainstream economists — and The Economist magazine since 1843 — have said: not really.

Among western economists, free trade is king. Even unilateral free trade (where the other side doesn’t return the favor) is often pitched to developing nations as better than playing tariff whack-a-mole. Free traders see tariffs as coddling inefficient domestic producers while punishing consumers. Trade is efficient. Trade is good.

The poster child for bad tariff policy is the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930. But was it the primary economy-killer that detractors claim?

Smoot-Hawley and Ferris Bueller

If you grew up in the 1980s, you heard about tariffs watching Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. The famous scene::

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which... Anyone? Anyone? …raised tariffs… Did not work and the U.S. sank deeper into the Great Depression.

That also is the consensus among the Twitterati. Bueller’s economics teacher is just reciting facts.

But here’s the twist: Most economic historians — including me — say that’s wrong.

There’s very little evidence that Smoot-Hawley caused or deepened the Great Depression. And there’s quite a bit of evidence it didn’t.

Let’s start with the fact that the U.S. was running a trade surplus in 1929. And in the early days of the Act, U.S. imports fell dramatically. Job done then? Not so fast. Exports also fell — by even more. And global trade was devastated.

But this was, after all, the Great Depression, and there were a number of important factors contributing to the decline in global trade. Deflation is one. Of course trade fell in monetary terms — the dollar was rising against almost all financial and real assets.

Also, global trade was just not that important in the grand scheme of things. Smoot-Hawley affected imports worth only 1.7% of GDP, according to Dartmouth economist Douglas Irwin. Further, goods not subject to tariffs also ended up being traded less in international markets. Imports and exports fell even on non-tariffed goods. The Depression was likely the cause — not the effect — of the initial decline in global trade.

High Tariffs, High Growth?

But if Smoot-Hawley wasn't the disaster we imagined, might tariffs actually have historical precedence for success?

There is a small group of development economists and historians who are more tariff-positive than the consensus. They have identified that periods of highest economic growth in U.S. history — and much of the Western world — also featured some of the highest tariffs.

During the Roaring 20s, for example, the U.S. and Spain had average tariff rates in the 40s, while the big three continental economies averaged around 21%. The U.K. was the outlier at around 5%, but Britain had other industrial policy tools.

It was actually Alexander Hamilton who coined the term “infant industry” and enacted policies to protect the U.S.’s nascent manufacturing sector — laws that survived until WWII. Lincoln raised tariffs to their highest levels yet after the Civil War. In this context, the Smoot-Hawley tariffs were not a huge shock, taking the average rate up by only six percentage points. For more than a century, the fastest-growing country was also the most protectionist.

And this was not an America-only phenomenon. Germany, Sweden, France, Finland, Australia, Japan, Taiwan, and Korea all grew rapidly behind increased tariffs and other trade barriers.

Correlation isn’t causation, sure — but clearly tariffs aren’t automatic economy-killers. In fact, the opposite might be closer to the truth. Tariffs may have helped make America great the first time.

Can Tariffs Make America Great Again?

The answer: Maybe. But probably not.

If tariffs are used selectively and strategically — as a form of industrial policy — they can work. Just ask South Korea. Or read Ha-Joon Chang. There’s an entire school of thought that says protectionism helped build modern economic powerhouses.

Even Adam Smith — the father of classical economics — left room for temporary protectionism when it helped strategic industries (e.g., the Royal Navy). And he believed in Trump’s idea of retaliatory tariffs to encourage negotiation toward freer trade (Wealth of Nations, Book IV, Chapter II):

“To expect that a country should trade freely when others do not, may be too romantic a notion.”

Tariffs performed, to some extent. Smoot-Hawley did indeed curtail imports — so much so that the Democrats didn’t repeal it when they regained power in Congress. House Leader Rainey was frank:

“We do not want this market flooded with the products of cheap labor from other countries.”

Sound like anyone we know this week?

So Why All the Vol?

Two reasons:

1. Retaliation

Tariffs don’t exist in a vacuum. This time, China retaliated immediately. So did Canada. (Try finding your favorite bourbon on Canadian shelves.) U.S. farmers buying potash (from Canada) and selling soybeans (to China) are going to suffer.

Douglas Irwin shows how Smoot-Hawley helped shatter America’s export reputation for decades. Trading partners — especially Canada and Britain — turned inward, and U.S. goods were viewed as politically risky. It took over 20 years to fix. How about this time?

2. Execution

Last week’s unprecedented approach was, and is, riddled with contradictions. Want to reduce the trade deficit? Tariffs might help. Want to use them to replace income taxes? Good luck — those two goals clash hard. Want to rewire the global supply chain or rebalance trade flows? That’s a fantasy — but we’ll go into that another time.

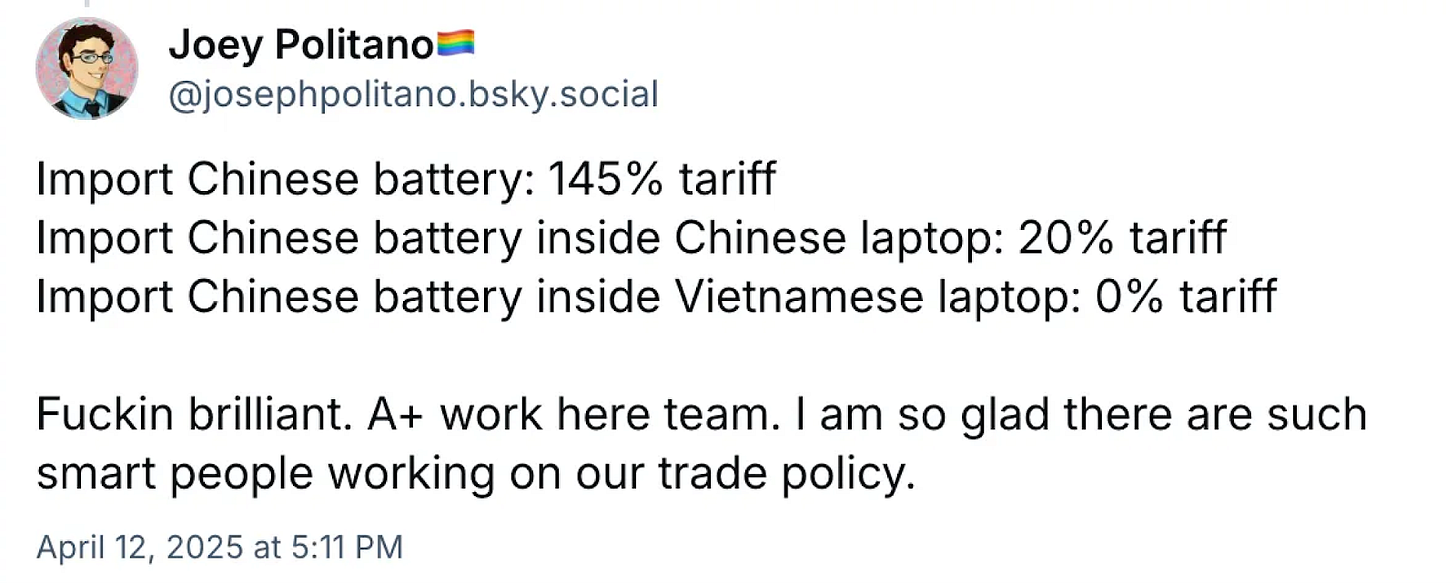

If there’s a game-theory model for how to fail at global economic diplomacy and industrial policy at the same time, the this White House may have found it. Tariff policy needs to be targeted. Potentially focused on strategic industries. And ideally, not run like a reality show. Certainly not like this:

The Bottom Line

The current tariff approach is certainly mock-worthy — poor execution, contradictions, and trade retaliation have overshadowed any potential benefits. Is the goal here to produce anything more than outrage?

Yet dismissing the idea outright may be premature. The idea of tariffs — when used strategically, sparingly, and as part of a broader policy — isn't crazy, even if 47 might be.

Strategic, targeted tariffs could indeed play a role in U.S. economic policy — but to get there, we need a smarter strategy, clearer goals, and fewer imaginary economists.

Next time: I go wonky with the U.S. Treasury market. Is the basis trade in trouble? Or is something bigger brewing?