The stock market is not evil, nor only for the wealthy, and certainly not something to abandon every time volatility hits. That’s cold comfort when you’re staring at a 20% loss—but it’s the truth.

It’s hard to stay sober when the markets – and your investments – look like they’re on an alternating combination of speed and sedatives.

If you tell people, "Here’s your retirement account this week..." and show this chart, that meeting should include herbal tea and breathing exercises.

A price chart like this is normally associated with the most speculative assets, like DOGE, GME, or Chamath’s SPACs..

Yet this is the chart of S&P 500 Index ETF, and the farthest right shows the April, 2025 tariff tantrum.

It should come with a bottle of Gravol.

It’s not just the ups and downs, but also the fact that the increased volatility usually comes with some serious market corrections. And correlation: Everything goes down. And generally pretty quickly. The move in the S&P ETF from 612 to 490 is almost exactly a bear market 20%, in less than a month.

The average young investor is likely to be in high-beta stocks, and as such is seeing even bigger swings in their investment portfolio. And they are more likely to be trading on borrowed money. As a result, Gen Z’s might be down more than the index’s 20%. And more worried.

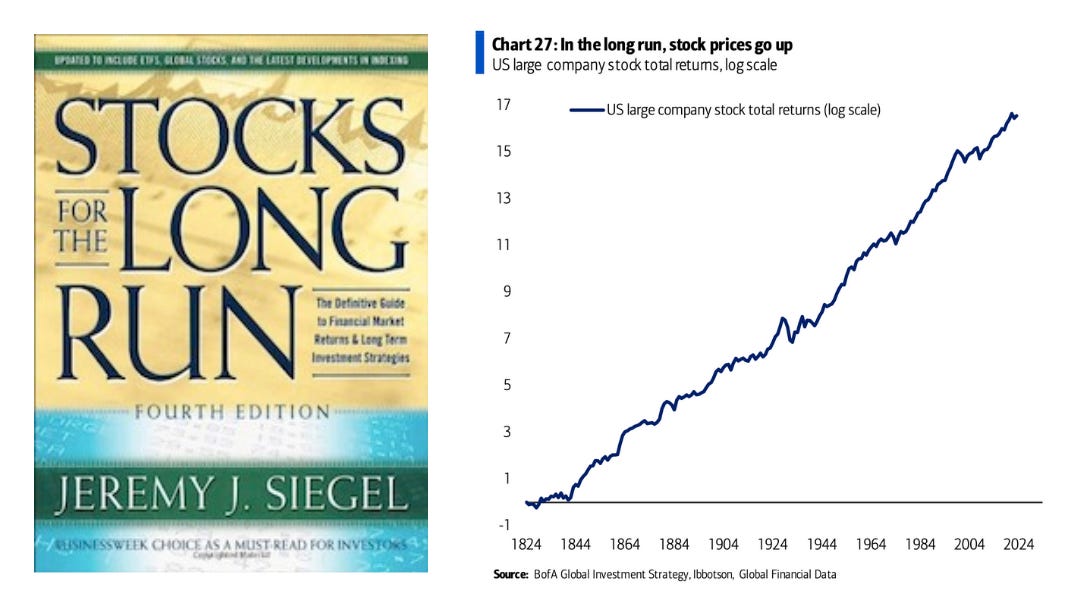

Stocks for the Long Run

Should you be worried? Yes and no.

Being caught in a short term correction feels horrible. You replay every should’ve and could’ve.

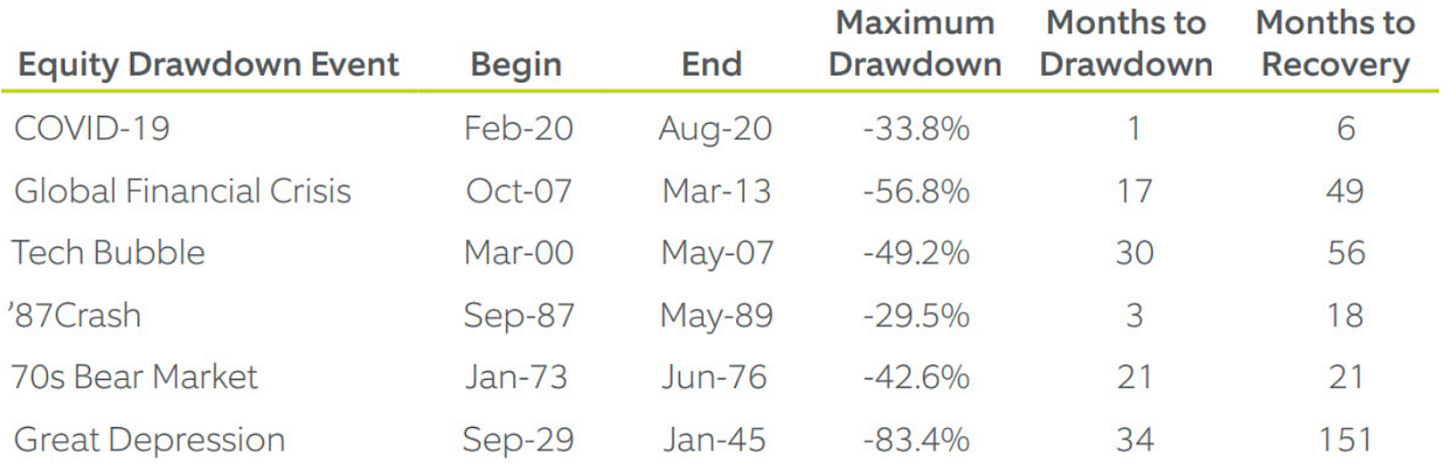

Being long stocks in a years-long decline is much worse. The tech bubble bursting took over two and a half years, with peak-to-trough drawdown of 49% in the S&P over cash. The GFC bear lasted a year and a bit, with a 56% decline, according to AQR’s Antti Ilmanen.

It never feels good to be down 50%. Trust me. We’ve been there.

But zoom out and the story changes. An investment in the S&P500 is an investment in the real economy of the financial powerhouse of the world. And that has been a good place to be for over a century. The US stock market has returned 10% per annum in nominal terms since 1925, and around 9% since WWII. That’s hard to beat.

While volatility is as natural as gravity, there are three key facts that shouldn’t be ignored:

Firstly, the longer-term chart shows 22 times the US stock market fell 20% or more. The latest was just under three years ago (do you remember?). Here are some of the most famous ones:

Drawdowns are generally followed by a long bull market, even if the recovery takes some time. The tech collapse took four years peak to peak (see above), but we all know what happened after 2004.

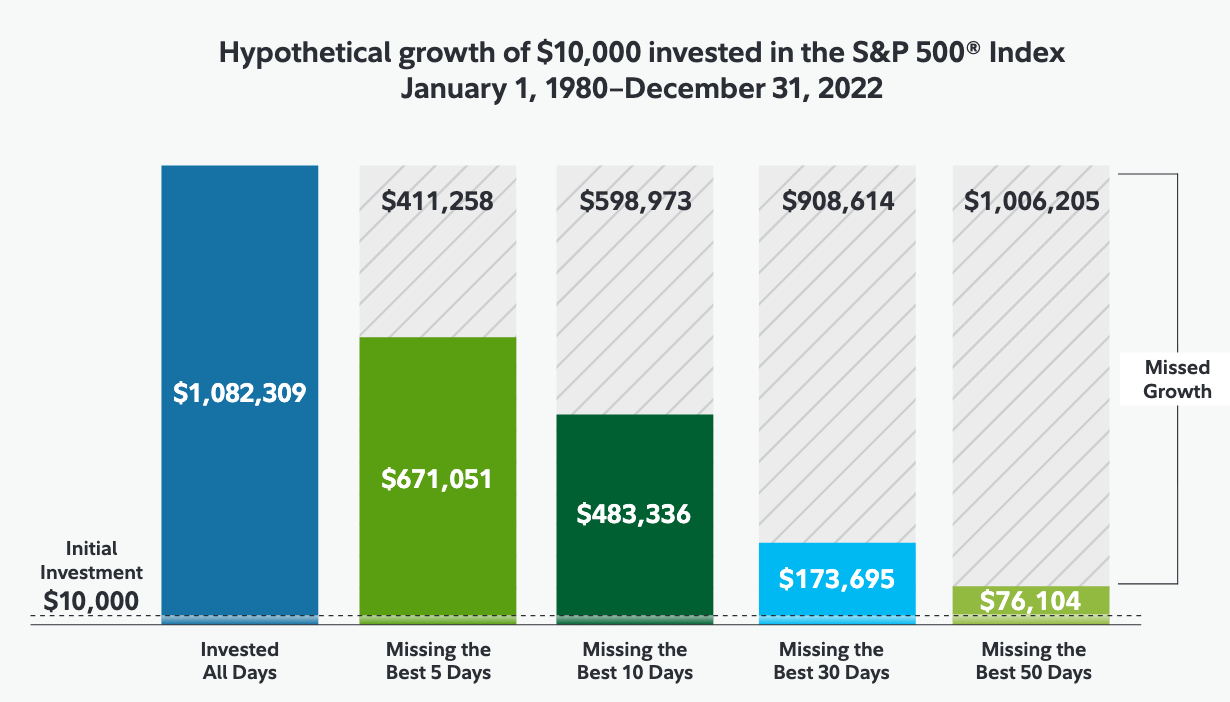

Secondly, some of the largest gains come within the bands of high volatility. Most of the best days in the market occur in bear markets. If you missed the 10 best days ever in the US stock market your return over the last century would have been 65% lower than the buy and hold portfolio. You would have given up two-thirds of all of the gains in the market, in its entire history. Just missing 10 days.

Let’s look at the modern era. No difference. Since 1980, missing the top 10 days would have halved your portfolio return:

Don’t miss those days.

Thirdly and finally, long-term investors spend more than 75% the time in a “drawdown state”. In the last few decades, over 25% of the time a buy and hold investor faced unrealized losses. That means an investor is often in a state of regret: “I could have bought lower”. Historically-speaking, being down big has been a temporary state of affairs. Patience was needed.

Bottom line is that, historically, being out of the market has been a risky move. Even if it took years to rebound (and lately it’s been less than that), staying in was the right call.

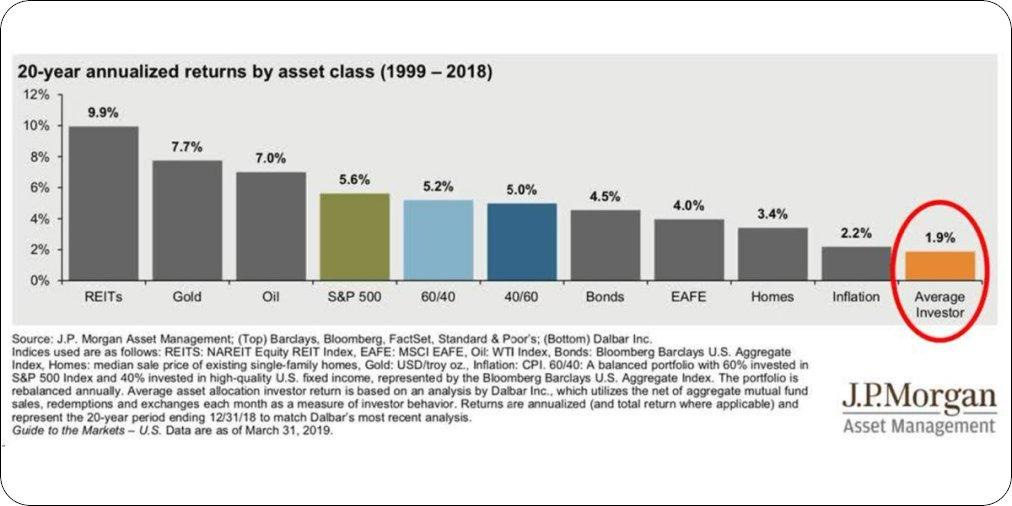

Getting hit with a large drawdown while then missing the rally due to skittishness is what has caused gross underperformance by retail investors.

Advisors Matter. Good Ones Even More

While I am generally against paying fees for something one can do themselves, during highly volatile times a rational and conservative financial advisor can do a lot of good.

The truth is that retail investors, left to their own devices, seriously underperform the market.

There are the fees, of course, but also it’s human nature to be fearful when others are fearful, instead of following the pre-eminent long term investor Warren Buffett’s advice to be greedy when others are fearful.

And then there are those advisors that encourage active trading. We hope you don’t know any of those. But sometimes the high fees associated with churning client accounts are too good to resist. But the big money in trading is made by owning a brokerage, or an exchange. There is a reason hedge funds pay for order flow.

Active trading can make one feel better about oneself. You feel in control of your own financial destiny, as opposed to being tied to the fates, and a capricious stock market.

The fact is that there are years and decades where stocks do not do so well. In every investor’s lifetime. And that feels horrible for investors. Nobody prepares investors for this. They haven’t seen the history. So they may just give up. And they generally give up just at the wrong time.

Frequent trading is unlikely to help. Yes, you might miss a down day or three, but you might also miss the rare melt-up. And the melt-up is where a lot of a decade’s profits can be made.

The successful active traders we hear about are rare anomalies or, in many cases, fictitious. They exist—but they’re as rare as alligators in Alaska. Yet everybody “knows someone” who made a killing.

The days of the stock-picking cowboy are long gone. Unless you are a large high-frequency trader with a view of the order flow, it’s hard to get an edge.

There are robots that can now do what advisors have done for decades, but none of them will spout anything but gibberish at you when markets are acting badly. Human advisors still have an important place, if only to pull clients off the ceiling. The psychological factor in investing should not be underestimated.

Simple Math, Big Results

The rule of seven says your money will double every seven years if it earns ten percent a year. That just happens to be the extremely long-term annual rate of return of the stock market. Every buy-and-hold investor with a cheap index fund and maybe a couple of their favorite company stocks has, inadvertently, kicked the butts of active traders, amateur or professional.

In a Crisis

We have good news and bad news. The bad news is that markets are volatile, and active trading doesn’t really cushion any bear market blow. Unless you are out of the market, and that feels more risky to me. The bottom line is that being long stocks is risky. And you could be in a drawdown for very long periods.

The good news is that, in the long run, things have worked out in the past. Investing in equities must be a long term play.

That means you treat money spent on stocks as funds you cannot have — so you’d better have an emergency cash stash.

Working with a good advisor, or hanging out with like-minded souls (or reading a blog like this one), can cushion the blow – and help you stay grounded.

Where will the market go next? We have no idea. And there I differ from many finance blogs out there, we guess.

We do know there will be rocky rides along the way. And that we want to stay in stocks for the long run.

Don’t panic. And always carry a towel. Not financial advice.